At the beginning of this month I told you about a book that had come out with some compelling information about the Polio epidemic that swept the country in the 50's, told from first person experience.

At the beginning of this month I told you about a book that had come out with some compelling information about the Polio epidemic that swept the country in the 50's, told from first person experience. The link to that post is HERE.

As a follow-up, I just received a Q & A from the author that gives some additional in-depth background on the book and the subject matter.

Enjoy!

___________________________________________________

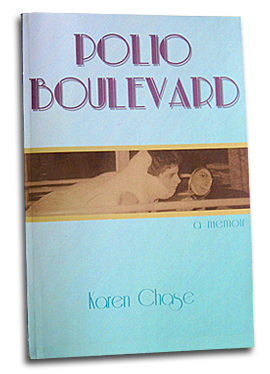

Q&A with Karen Chase, author of POLIO BOULEVARD

Sixty years after your childhood polio diagnosis and after a long,

successful career as an author of poems, stories and essays, why did you finally

decide to write your memoir, POLIO BOULEVARD?

While

my childhood was marred by the disease and its recovery, I did not consciously

think of myself as a polio survivor. For many decades, I never looked back. My

polio became a distant memory. I suppose it has taken me this long to write

about it because, for some people, personal stories take a long time to

tell. Although I didn’t experience my

illness as traumatic, no doubt it was.

Maybe I repressed the story. For

some reason, it never popped up as something to talk or write about. Art being what it is – art emerges from the

soul – it suddenly loomed large as a subject to explore in my writing. I don’t question this process. I just tag along, following the muse.

What was your childhood like prior to your polio diagnosis?

I

was a sprouting ten-year-old girl living in an affluent suburb of New York City,

and all was well. I was merrily jumping rope and playing hopscotch with my

friends. I’d hop on my bike and help my

older brother deliver newspapers up and down the streets of my town. I’d swim

in Long Island Sound, a short bike ride from our house. And I had a new baby

sister! I was in fifth grade. One day

while walking home from school for lunch, kicking a stone down the road, my

legs began to hurt. After a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and glass of cold

milk, I said, “Mom, I can’t go back to school today.” My neck got stiff, my

fever rose alarmingly, and what started as small pains turned into large ones.

The doctor came and soon I was rushed to the hospital in an ambulance,

diagnosed with polio.

What was the recovery process like?

I

spent 6 months in Sunshine Cottage, the polio ward at Grasslands Hospital in

Westchester County, NY. During that

time, I was in a wheelchair and had a back brace. Later, I was put in a

full-length body cast, underwent a spinal fusion at the Hospital for Special

Surgery in New York City. I left school in fifth grade upon my diagnosis and

did not return until I was a high school freshman.

How did your rich imagination and creativity help you through your

ordeal?

As

a young girl, my mother took me on the train into New York City where I took

painting lessons in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum. Right now, I can

smell those oversized jars of red and blue tempera. I loved to paint. Polio

struck when I was ten years old and I was shocked to be immobilized—first by

the deadening effect of polio and later by an enormous body cast. As my body

was losing motion, my mind was painting. I remember lying inert in my hospital

bed, focused on the dots of the hospital ceiling tiles. I pretended they were all kinds of animals on

the move—bears, camels, foxes on parade. With the help of my abundant

imagination, I joked around on the hospital ward, making life not only bearable

but fun. Looking monster-like in my full-length body cast, I wrote a letter to

the Barbizon School of Modeling, asking whether I could become a model. My illness

made for a rich inner life and immobility shaped and widened my vision. After

polio, I valued my mind’s flexibility like gold.

How did having polio as a child affect your sensory experiences and

body image?

The

way a blind person compensates for for lack of vision by exceptional hearing, I

compensated for my immobility by always looking, looking, looking and always

listening. Before I got sick, I was particularly tuned in to what I saw and

heard. Since then, this tendency has

mushroomed. To this day, I react strongly to even the slightest sound, which

can sometimes be difficult. When I hear friends talk about aging, how this or

that attribute has changed, I realize how my polio has affected my body image.

My body has been imperfect for as long as I can remember. Seeing my body age is part of this ongoing

imperfection so it is not jarring. I

don’t mean to sound like I don’t care what I look like – I’m actually quite

vain.

What was your reaction to the news that Jonas Salk had invented the

polio vaccine?

In

the spring of 1954, when I was a patient in the polio ward at Grasslands

Hospital in Westchester County, I was happily playing Monopoly with my friends. The radio was on. A voice announced that a doctor named Jonas

Salk had invented a vaccine to prevent polio.

Some of us turned silent, some of us laughed, and one patient blurted

out, “Too late for us!” Here we were, a

group of ill children on stretchers and in wheelchairs living through an

historical moment when polio’s peril was replaced by joy and relief.

What has been your personal perspective over the years on Franklin

Delano Roosevelt, a polio patient who became president of the United States?

For

me and so many others who had polio, FDR is a figure alive in our imaginations.

How helpful to know how he embraced life after his illness, how courageous he

was, how he moved ahead in the world. Not only that, but the way he tirelessly

worked and fought for those less fortunate is inspiring, especially in today’s

climate. Additionally, my parents were

lefty liberals and adored Roosevelt.

There were plenty of books around our house about him, making him a

familiar character. I have always felt a

kinship with him, almost like we are part of the same family, almost like he is

my grandfather. In fact, writing POLIO

BOULEVARD, a book in which FDR is an important character, has led to my current

writing project.

What has your reaction been to hearing that polio is back in the news

as a global threat again?

That

children in Pakistan, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq wake up in their

beds with pain and fever as polio invades their bodies and does its deadly work

is a devastating thought. How can this be? Because of the preventative power of

the Salk Vaccine, it is avoidable. The World Health Organization, the Bill and

Melinda Gates Foundation, and the International Rotary Club have dedicated

themselves to making the earth polio-free.

Through their efforts and their dollars, combined with many countries’

internal efforts, polio has been eradicated in most of the world. Recently,

while spending time in New Delhi, I saw billboards that publicized polio as an

existing threat. But I also learned that the Indian government was sending out

massive numbers of people to families and religious leaders in order to foster

understanding about immunizations. Aid

workers were being sent to the most remote villages in the country to dispense

the vaccine. Even Bollywood stars and celebrity cricket players joined in. Huge

efforts from within the country, combined with international dedication, have

made India polio-free as of 2013, making India a prime example of how polio can

be stricken from this earth.

What are your views on the current parental trend in vaccine hesitancy?

During

my childhood, polio terrified the country, killing and crippling at random. It

lurked anywhere, came on as easily as a cold. Any fever, stiff neck or sore

throat caused hysteria. Parents of young children today cannot imagine what a

deadly epidemic is like. If you’re

reading about the Ebola virus spreading through West Africa right now and the

alarm that is causing, you can begin to understand the terror of polio. Today,

a controversy swirls around the subject of vaccines. To me it is clear: it is a

basic public health service for the government to require children to be

vaccinated against polio. Society needs such protection. Considering my

childhood ordeal, I cannot imagine forgoing the protection the polio vaccine

provides.

What do you hope readers take away from POLIO BOULEVARD?

First

and foremost, I hope readers find this a good, exotic, well-told story that

they can’t put down. I hope that the story encourages those who are ill or have

ill children to try to focus on what’s positive in the situation, and not to be

defined by it. You are who you are, no matter the illness, and it helps not to

lose that sense of yourself. This brings

me to the reason the book appeals to young readers. To read about a serious obstacle in life that

doesn’t touch you directly – it’s in a book!

– is one way of conquering and mastering fear. People like to read about

disease and I hope that the story of my childhood illness shows how even in the

throes of serious disease, one can be confident, have fun and live a good life.

I also hope that those vaccine-hesitant parents who struggle with the issue,

will find the story of my illness thought provoking, in terms of what is was

like to live in a culture with an ongoing horrifying epidemic.

What are you working on next?

Franklin

Delano Roosevelt makes many appearances in POLIO BOULEVARD and now has become

the sole focus of my current writing project.

Three years after he was stricken with polio, he bought a houseboat with

a friend and named it the Larooco. From

1924-26, he spent a few months each winter in the Florida Keys on the

boat. While there, he kept a nautical

log, writing longhand each day about fish caught, weather, the boat’s route,

engine trouble, guests, and meals. The Larooco Log is entrancing and is the centerpiece

of my new project.