Funny what a five year-old remembers.

Many years pass and the mental playback is still rich in full sensory depth; smells, colors, and sounds release all in a jumble. And stranger still, the memory retains the smallness of one's self; people and things forever etched as much larger than real life. Isn't it a mystery how an adult brain can wrap around a long ago event and keep the little child's perspective?

Revisiting old haunts and physical places of my past brings a pouring of memories, but the puzzle pieces aren't quite right. Surely that porch was much wider, much more shadowy in the recesses? That swing surely flew much higher? The long ago recollections contrast jarringly when viewed again with adult eyes.

Several years ago, I drove down Gould Street looking for landmarks, something to help me remember the little girl I once was; perhaps for 1959.

I didn't find either, at first. The neighborhood had changed, houses cheaply remodeled, losing all their quaint charm and warmth in the process. The faces looking back at me from the windows and doors were brown; sounds of latino music blared rudely from a garage or backyard.

My Aunt Minnie's house was unrecognizable at first. The grand old front porch with its shiny gray enameled painted floor and the low jutting brick structures lining the sidewalk were all gone. No flowerbeds full of roses (where my brother once fell and ruined his Easter white coat just as the church bus pulled up to take us to Sunday service), no fig bushes at the corners, no fragrant mulberry tree staining the ground an odd color of purple - the overripe berries polka-dotting the sidewalk, and no detached whitewashed garage secretly harboring an old Model A Ford.

By counting the houses from the corner, I could determine the one I sought. Nothing else of memory could have guided me. Parking along the curb, with the car windows rolled down, I closed my eyes. Surely the familiar scent of the old sycamore trees, their curious peeling brown bark revealing white tender trunk wood and the hard woody-balled fruits that turn to wispy seed puffs when broken up, would still be wafting on the late summer wind. No. There were no long rows of sycamores left growing next to the cracked and disappearing sidewalks.

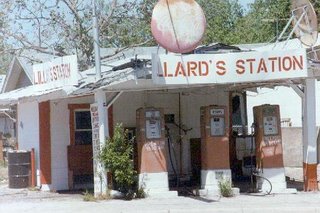

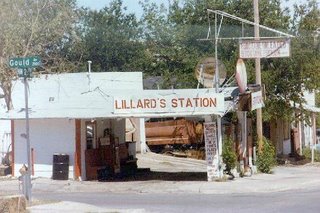

Slowly I drove down to the corner of 25th and Gould. On my left should have been Lillard's Station. Sadly, it too had left with the sycamores, and Mr. Lillard long gone to that filling station in the sky.

He was a quiet fellow with a slow grin; his attire and his countenance matching with the weatherworn design of hard work and low wages. The old station had no concrete running underneath the tin awnings, just dirt hardpacked with years upon years of old engine oil poured on top. The hot summer sun would suck the grease up to form tiny droplets, painting the bottoms of our bare feet in a matted black ink, causing us to leave faint footprints on the sidewalk when we trudged back home. We would laugh and walk backwards a few steps, then forwards, thinking we were oh so clever. That old oil coupled with mushed mulberries stained our feet for months long into fall.

Aunt Minnie was diabetic, so the afternoon treat of soda pop usually meant a Diet Rite Cola for her. My brother and I pondered long after awakening from our regimented lunchtime nap on what we would get, maybe a Nehi or a Frostie, but more likely an RC Cola which looked like it had double the amount of pop in it. Gathering up three bottles to save the two cents deposit, we would walk down to Lillard's. Aunt Minnie sat watching from her rocker on the front porch - occasionally walking with us if we were in one of those sibling moods where one of us had to have "the last touch" and usually erupting in full-fledged fist fights. Those days she walked with one of us on each side of her, a firm grip on our arms. Sneaking looks behind her back, we would glare and stick out our tongues at each other, until my brother made some goofy face and we would start giggling uncontrollably. Either way, we were not allowed the freedom to fetch the treats by ourselves unless our behavior warranted a reprieve.

The essence of what I sought was not physically there any longer, but my five year-old self jumped up to fill in the missing colors. All I had to do was slow down and encourage her to speak up. At first it was in little childish half-whispers, until finally her impatient urging of "don't you remember?" pushed long forgotten days into recognition.

As I drove away from Gould Street, I could almost see her in the rearview mirror- skipping on the sidewalk, a soda grasped in one hand, white blonde wisps of hair sticking to the corners of her mouth, and purple feet shining back at me with each running step.

(* The wonders of the internet - I found these photos of the real Lillard's Station and they are the reason for this post. Obviously, these pictures were taken long after the closing of the old station and reflect the dereliction of the neighborhood.)